Searching for the Lost City of Copper

- infonorthcyprus

- Apr 4, 2017

- 3 min read

Rich in copper, skilled in bronzework, Cyprus was courted as a trading partner all over the ancient world. So why did it take so long for archaeologists to discover one of its greatest cities?

“To the King of Egypt, my brother. Thus says the King of Alashiya, your brother: ... Send your messenger along with my messenger quickly and all the copper that you desire I will send you.”

Dating to 1375 B.C., these words are from the collection of tablets known as the Amarna Correspondence, a cache of diplomatic exchanges discovered in the late 19th century. Historians identify the king of Egypt as Akhenaten, but who was writing to him? And where was Alashiya?

Many historians feel that the most likely candidate for copper-rich Alashiya is in Cyprus. But the story of identifying the lost city near the modern-day Cypriot village of Enkomi is filled with archaeological blunders and near misses.

It is now known that during the Late Bronze Age, from the 15th to 11th centuries B.C., the Enkomi site was one of Cyprus’s significant cities, a center of the copper trade, which was the island’s main source of wealth. Unlike the nearby ancient city of Salamis whose Roman ruins stand to this day (not to be confused with the Island of Salamis just west of Athens), few traces of the ancient site now known as Enkomi remained.

Mistaken Identities

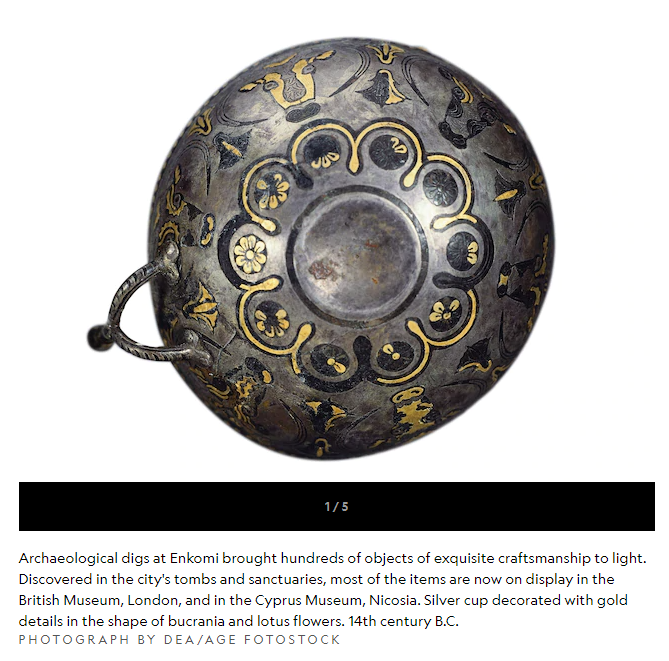

The first dig began in 1896 at a site located in what is today Turkish-controlled Northern Cyprus. It was led by Alexander Murray, the British Museum’s leading Greco-Roman expert. Murray’s work revealed an extensive necropolis with around a hundred tombs containing gold, silver, bronze, and marble objects, faience (tin-glazed earthenware), and precious stones. Although he considered the tombs to be very old, the medieval ceramics he found led him to misdate the site. Murray believed the signs of urban settlement were from around the 13th or 14th century A.D.

This erroneous late dating meant that later digs at the site failed to make proper historical connections. In 1913 John Myres, an Oxford University professor and a highly regarded authority on Cypriot archaeology, undertook a three-month exploration of the site, and unearthed a series of extensive city walls.

Later, Myres expressed regret for calling a halt to the work despite recognizing at the time that the walls were neither Byzantine nor Greco-Roman. They seemed to be part of a much more ancient city to which the necropolis belonged.

A later dig, conducted by the Swedish archaeologist Einar Gjerstad in 1930, worked on the assumption that the city associated with the tombs would be in another part of the site altogether. His team failed to realize that the necropolis and the city were actually intertwined.

Years later he acknowledged his blunder: “I was working on a pre-conceived idea. Since burial-grounds and settlements were ... separated, as far as was known, during the whole Bronze Age in Cyprus, there was no reason to suppose that there were other habits in Enkomi.”

Finding the Answers

Much of the puzzle of Enkomi was finally pieced together under the team led by French archaeologist Claude F. A. Schaeffer. Educated at Strasbourg and Oxford, Schaeffer excavated in 1929 the ancient city of Ugarit, located on the Syrian coast opposite Cyprus. The abundance of Cypriot material found there led him to explore the ancient cultural ties between Ugarit and Cyprus. Schaeffer would later direct the long-running archaeological expedition in Enkomi until 1970, assisted by Porphyrios Dikaios, curator and later director of the Cypriot Department of Antiquities.

The Schaeffer-Dikaios partnership established that the necropolis developed in and around a bustling ancient city, which peaked between 1340 and 1200 B.C. Surrounded by a wall built using the “cyclopean” technique of massive stone blocks, it consisted of dwellings, temples, and workshops where copper was processed and bronze items produced.

So was Enkomi the principal city of the copper-rich Alashiya mentioned in the Amarna Correspondence? In 1963 the discovery there of a bronze statuette of a divinity standing on a copper ingot seemed to support this theory.

In 1974 Cyprus was invaded by Turkey, who occupied the northern part of the island—a disputed situation that continues to this day. Schaeffer’s successor, Olivier Pelon, who had taken over in 1970, was forced to suspend the dig.

Since then, while most historians believe Cyprus is indeed the Alashiya of antiquity, new research has called into question Enkomi’s status as a “capital” or principal city of this wealthy state.

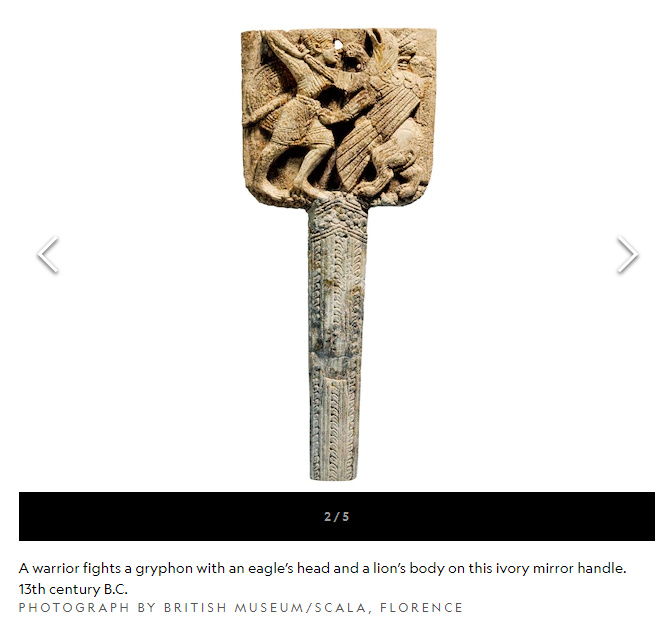

To judge from the large range of exquisite objects in museums such as the British Museum, however, Enkomi must have been a sophisticated urban center. Around the 11th century B.C., the city was abandoned while the city of Salamis rose to prominence, becoming the principal Cypriot trading center with Egypt and the rest of the eastern Mediterranean.

Cypriot Splendor

Source: National Geographic https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/world-history-magazine/article/enkomi-cyprus-ancient-city-copper-bronze?fbclid=IwAR2R_ppqt4g8TiX0mOaUKRJXlG9fm_177TA_Y0-5T90Ed_yesw-592zpUw0

Comments